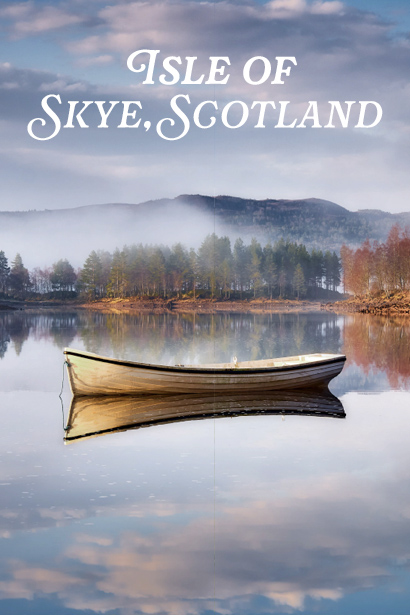

Explore the enclaves of Beirut, Lebanon

Taste classic flavors of Lebanon

“Little Armenia”

The city unfolds through the heady aroma of freshly cut kisbara (coriander), za’atar (an earthy toasted spice mixture) and unleavened flatbread known as markouk. The turbulent history of the city and its distinctive neighborhoods is best explored through its diverse, delicious cuisine. All the walks I take in Beirut lead me to its Armenian enclave, Bourj Hammoud. The neighborhood is an integral cornerstone of the city’s culinary world. A tightly woven, salt-of-the-earth patchwork of densely populated streets, Shi’ite mosques, fragrant spices and butter-laden pastries, Bourj Hammoud is not for the faint of heart. When I cross the river into its colorful environs from Beirut proper, I feel like I’ve crossed state lines, or tumbled into another era, or country. In a way, I have. In the first two decades of the 20th century, after the collapse of the Ottoman Empire and in the wake of a genocide that claimed nearly two million lives, Armenians began to scatter across the world, and Bourj Hammoud was one of their most crucial refuges. It began as a refugee settlement, but over the decades it became a bustling micro metropolis; it’s now known as Beirut’s “Little Armenia.”

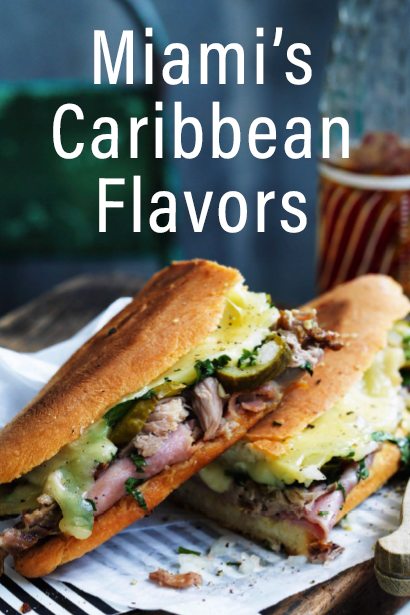

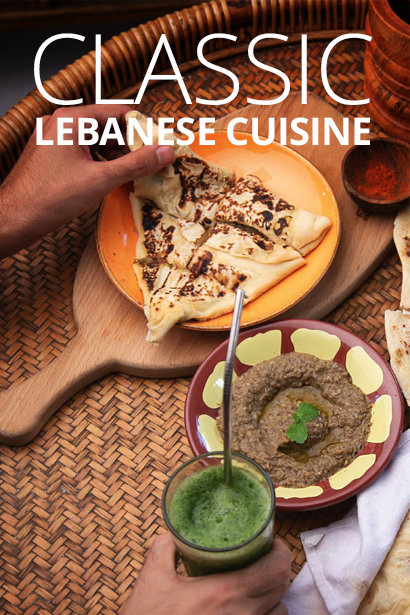

Lebanese mezze

Quintessential Bakeries

Among the old men in hats playing tawlet (backgammon) and the children jostling their way through the throngs of mopeds carrying assorted deliveries — my day begins. In the morning, the edges of the city are softer, and on this clear day the sunlight spills onto the buildings. I choose to walk down Marash and Arax Streets, the enclave’s two main arteries. No matter how much time I spend here, I’m still thrilled by the abundance of shops selling loofahs, sundry goods and vine leaves. I head to select from Bourj Hammoud’s finest establishments, its restaurants and furns (bakeries). The best choices are Ghazar Bakery and Hovig Bakery, both offering excellent fare. They serve a quintessential on-the-go Lebanese breakfast: a manakeesh (savory pastry) with its myriad toppings — cheese and za’atar, or spinach and keshek (yogurt fermented with bulgur, often mixed with chilli paste and sesame seeds). It’s possible to pick one up from outposts all over the city, and the debate over which is the best is never-ending. But I’m in Bourj Hammoud, and around me the breakfasts are vast and varied. From the window of Ghazar Bakery, situated on a car’s-width back street, I watch as steaming lahm bi ajeen (literally translated to “meat with dough”) is dished up to ravenous diners. Some people like to call it the local version of a pizza, but lahm bi ajeen is more of a savory pastry.

Sometimes it’s served plain; other times, it’s accompanied by pomegranate molasses or the meat is swapped for mushrooms. I sidle up to the counter with my ayran (salty yogurt-based beverage) and watch as the streamlined operation unfolds. The synchronization of the workers in front of the wood-burning oven is mesmerizing. Satiated but not full, I wind through the back streets, shadowed by billowing flags and dangling baskets to Hovig Bakery. Here, you’ll find the full spectrum of Bourj Hammoud society, and the legendary Armenian pastry tahinov hatz. A swirly, sweet bread made of tahini, sugar and cinnamon, making tahinov hatz is a delicate business and Hovig’s has mastered it. It’s best paired with a coffee with condensed milk from the dekkane (mini market) across the road

Beirut’s Intellectual Hub

My next stop is Hamra in West Beirut. During the Lebanese Civil War, Beirut was divided by a line of demarcation called the Green Line. It separated East Beirut, which is where Bourj Hammoud is located, from West Beirut. Such lines no longer exist, but their psychogeographical legacy does. Walking across, this dark part of the country’s history is inescapable. Hamra, before the 1990s, was the preeminent intellectual hub of the city. The hollowed vestiges of those former haunts remain, with new ones like the bookstore and library Barzakh sprouting up. Its selection of no-frills food venues is superb, too.

Café break

Flavors of Beirut

Traditional Cuisine

Starting at Al Sharif, my first choice is for a taste of some of the best fatteh (yogurt, chickpeas, pine nuts and tahini topping toasted flatbread) in the city. It’s traditionally eaten at breakfast, but for me it's a hearty lunchtime pick-me-up. I continue farther west along the main road toward the sea, to Hammandi. This is a butcher and a sandwich shop popular with the local crowd. The classic Beirut dish shish tawouk (marinated chicken shish kebab) is excellent here, but the sujuk (spicy dry cured sausage) sandwich is supreme. I remember the words I heard from Roy Hankach, a Lebanese sausage-maker. “It’s very difficult nowadays to find good sujuk sandwiches — Hammandi makes the best I’ve ever had.” His version strays from the traditional style, topped with a little mayonnaise, but I love the addition. The alteration makes it more reminiscent of my childhood favorites — Lebanon's relationship with its food, like my own, tends to be deeply nostalgic.

Seek out the late-night scene

Beirut’s Nightlife

My next destination, the district of Mar Mikhael, is particularly charged with memories. What used to be a working-class, industrial neighborhood has, over the past decade, become one of the epicenters of Beirut’s nightlife. It’s also where I go to visit one of my favorite cocktail bars, tucked away on one of the unassuming side streets.

The bar is called Anise, a dimly lit enclave that leans on a Prohibition-era aesthetic. It’s easy on the eyes, and the staff’s knowledge and expertise is extensive. Beirut has long been known as one of the Middle East’s best nightlife destinations. Maybe it’s not a stiff competition in the largely sober region, but its local mixologists are still dedicated to keeping the mood up in the unpredictable city. Despite that, I decide to keep it simple with a classic cocktail. I keep it light — I’m dining at the inimitable Varouj after. Varouj is another Beirut institution — it deserves a whole tome of its own. With just five tables, this intimate, shoebox-sized restaurant has seen all classes of Lebanese society walk through its doors. I’m ordering a spread — marinated sheep testicles, the meat of several small birds, offal and more. It’s traditional Armenian fare, especially enjoyable paired with some manti (small dumplings) and muhammara (roasted red pepper dip). Each bite is a reminder of Beirut’s countless diasporic communities, and the food that developed in the mix.